Copper killing improved

Australian engineers have come up with a copper surface that eliminates bacteria in just two minutes.

Australian engineers have come up with a copper surface that eliminates bacteria in just two minutes.

They say the surface can destroy bacteria more than 100 times faster and more effectively than standard copper.

It could help combat the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

Copper is used to fight bacteria because the ions released from the metal’s surface are toxic to their cells. But this process is slow when standard copper is used.

RMIT University’s Distinguished Professor Ma Qian says significant efforts are underway by researchers worldwide to speed it up.

“A standard copper surface will kill about 97 per cent of golden staph within four hours,” Qian said.

“Incredibly, when we placed golden staph bacteria on our specially-designed copper surface, it destroyed more than 99.99 per cent of the cells in just two minutes.”

“So not only is it more effective, it’s 120 times faster.”

Importantly, said Dr Qian, these results were achieved without the assistance of any drug.

“Our copper structure has shown itself to be remarkably potent for such a common material,” he said.

The team believes there could be a huge range of applications for the new material once further developed, including antimicrobial doorhandles and other touch surfaces in schools, hospitals, homes and public transport, as well as filters in antimicrobial respirators or air ventilation systems, and in face masks.

The team is now looking to investigate the enhanced copper’s effectiveness against SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Other studies suggest copper may be highly effective against the virus, leading the US Environmental Protection Agency to officially approve copper surfaces for antiviral uses earlier this year.

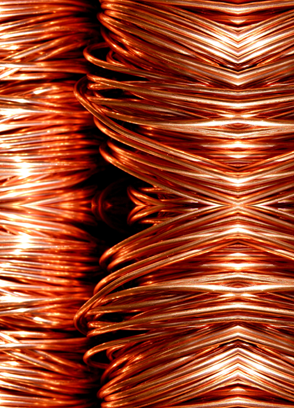

Copper’s unique porous structure is key to its effectiveness as a rapid bacteria killer.

In the latest research efforts, a special copper mould casting process was used to make the alloy, arranging copper and manganese atoms into specific formations.

The manganese atoms were then removed from the alloy using a cheap and scalable chemical process called “dealloying”, leaving pure copper full of tiny microscale and nanoscale cavities in its surface.

The copper material is composed of comb-like microscale cavities and within each tooth of that comb structure are much smaller nanoscale cavities, giving it a massive active surface area.

The pattern also makes the surface super hydrophilic, so that water lies on it as a flat film rather than as droplets.

The hydrophilic effect means bacterial cells struggle to hold their form as they are stretched by the surface nanostructure, while the porous pattern allows copper ions to release faster.

These combined effects not only cause structural degradation of bacterial cells, making them more vulnerable to the poisonous copper ions, but also facilitates uptake of copper ions into the bacterial cells.

“It’s that combination of effects that results in greatly accelerated elimination of bacteria,’ says former CSIRO researcher and study lead author, Dr Jackson Leigh Smith.

More details are accessible here.

Print

Print