Cancer revamp considered

Experts are debating whether low risk cancers should be renamed to make them sound less scary.

Experts are debating whether low risk cancers should be renamed to make them sound less scary.

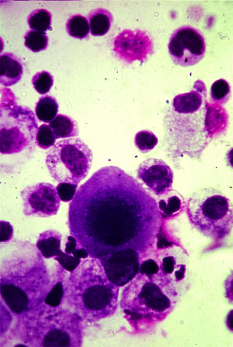

The clinical definition of cancer is a disease that, if untreated, will grow relentlessly and spread to other organs, killing the host.

Yet what we routinely refer to as cancer today is a disease ranging from ultra low (less than a 5 per cent chance of progression over two decades) to extremely high (more than a 75 per cent chance of progression over one to two years).

There has been a significant increase in the detection and treatment of ultra-low risk cancers, including many thyroid, prostate, and breast cancers.

Up to 35 per cent of all screen-detected breast cancers fall into the ultra low risk category, yet women with low risk lesions (known as ductal carcinoma in situ or DCIS) “are being rushed to the operating room, precipitating a lifetime of anxiety,” says Laura Esserman at the Carol Franc Buck Breast Care Center in San Francisco, California.

Investigation and invasive intervention themselves carry risk. Rather than surgery, she believes we should offer active surveillance, but says; “it is difficult to encourage patients to wait and watch once they have been told they have cancer.”

Overtreating people who are not at risk of death “does not improve the lives of those at highest risk,” she writes in a discussion piece for the BMJ.

“The refinement of the nomenclature for cancer is one of the most important steps we can take to improve the outcomes and quality of life of patients with cancer.”

Dr Murali Varma from the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff says creating new entities risks confusion.

It is impossible to determine the natural course of any low risk tumour, he says, “because excision for definitive diagnosis alters its natural course, precluding knowledge of how the tumour would have behaved if left untreated.”

This uncertainty could also lead to underestimation of the frequency of overdiagnosis as some “cured cancers” would not have progressed even if untreated, he adds.

Dr Varma says the key is to educate everyone from the public to health professionals about the meaning of a diagnosis of cancer, not mess around with semantics.

New terminology often leads to confusion, so an alternative approach would be to recalibrate thresholds for the diagnosis of cancer, so that some very low risk cancers are categorised as benign, he suggests.

“If the public were educated that benign signifies very low risk rather than no risk at all, then anxiety inducing labels could be avoided,” he concludes.

Print

Print