Cell study reveals chemo target

Scientists have discovered that cells inject each other, which could open a new line of attack on cancer.

Scientists have discovered that cells inject each other, which could open a new line of attack on cancer.

Most cancer cells are killed by chemotherapy, but their individual variation means some escape. So, diversity among cancer cells is an issue for cancer treatment.

Previously, diversity was thought to be mostly due to genetic variability among cancer cells. But now, University of Sydney researchers have discovered a whole new source of cancer cell diversity.

In 2012, it was discovered that cancer cells exchange contents with surrounding normal cells called fibroblasts, but the mechanism remained unknown, until now.

Professor Hans Zoellner from the University of Sydney, who made the initial 2012 finding, can now explain how.

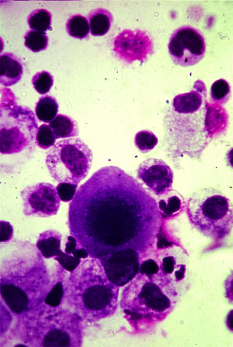

All cells constantly probe each other with tentacle-like cell-projections. These reach out to neighbours, probe, and then retract, as part of the way cells sense their environment.

When a cell-projection retracts, there is a brief increase in fluid pressure within the projection, to force cytoplasm – the jelly-like fluid within the cells – back into the cell body.

Studying cells in time-lapse movies, Professor Zoellner noticed that transfer is from retracting cell-projections.

He reasoned that transient micro-fusions between the retracting cell-projections and any neighbouring cell, would permit cytoplasm from the cell-projection to be injected into the neighbour, instead of being returned to the fibroblast.

His team tested this idea by combining mathematical modelling, cell experimentation, and computer simulation. The outcome was the discovery of what seems to be a previously unknown biological mechanism, now coined ‘cell-projection pumping’.

They found that cancer cells become more diverse in size and shape, and also migrate more quickly, after cell-projection pumping. Importantly, preliminary results show a further effect, resisting chemotherapy.

The work continues, and Dr Zoellner says: “This is a whole new cancer target. Now that we know it’s happening, we can think about trying to block it, and work towards better outcomes”.

“This has been a tough project, stretched over 19 years, and very hard to fund, but I’m glad to have such wonderful colleagues, and proud of my team’s persistence.”

The results have been published in the Biophysical Journal.

Print

Print