Robo-spleen set to take swing at sepsis

Researchers have developed a robot spleen to fight sepsis – a major cause of deaths in intensive care.

Researchers have developed a robot spleen to fight sepsis – a major cause of deaths in intensive care.

The ‘biospleen’ is inspired by its human equivalent, working to cleanse blood of the bacteria and fungi that multiply rapidly during sepsis.

Sepsis kills around eight million people worldwide each year and has been the leading cause of hospital deaths for years.

“Even with the best current treatments, sepsis patients are dying in intensive care units at least 30 percent of the time,” says bio-engineer Dr Mike Super.

“We need a new approach.”

Early tests have impressed even the designers.

In a matter of hours, the biospleen can filter live and dead pathogens from the blood, as well as dangerous toxins that are released from the pathogens.

The micro-fluidic device works outside the body like a dialysis machine, removing living and dead microbes of all varieties.

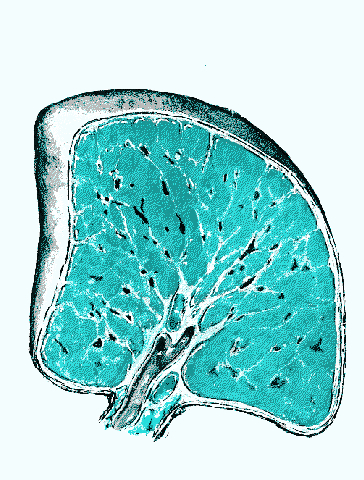

It is modelled on the microscopic architecture of the human spleen, which a series of tiny interwoven blood channels to remove pathogens and dead cells from the blood.

The biospleen consists of two adjacent hollow channels that are connected to each other by a series of slits; one channel contains flowing blood, and the other has a saline solution that collects and removes pathogens as they travel through the slits.

Tiny nanometre-sized magnetic beads hold the key to the design. They are coated with a genetically-engineered version of a natural immune system protein called mannose binding lectin (MBL).

MBL binds itself to specific sugars on the surfaces of bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa and toxins, and then cues the immune system to come and destroy them.

The biospleen was tested on human blood spiked with pathogens in the laboratory.

It was able to filter blood much faster than ever before, as the magnets efficiently pulled the nano-beads coated with the pathogens out of the blood.

In fact, more than 90 percent of key sepsis pathogens were bound and removed when the blood flowed through a single device at a rate of about a half to one litre per hour.

Researchers say a series of devices can be linked together to obtain levels required for human blood cleansing at the same rate as dialysis.

“We didn't have to kill the pathogens. We just captured and removed them,” Dr Super said.

In later tests using laboratory rats, 90 per cent of those treated survived, compared to 14 per cent of the control group.

The work was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Dialysis-Like Therapeutics program and Harvard University.

Print

Print