Study shows cellular cross-talk

Australian researchers have uncovered a kind of communication between breast cancers and normal cells that encourage the cancer to become more aggressive.

Australian researchers have uncovered a kind of communication between breast cancers and normal cells that encourage the cancer to become more aggressive.

Researchers at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research and Adelaide’s Centre for Cancer Biology analysed the genetic output of thousands of individual cells within a tumour.

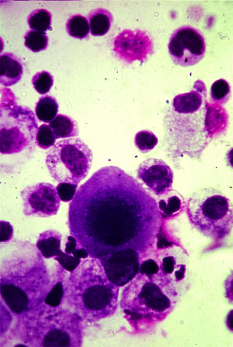

Importantly, they found that cancer cells send signals to neighbouring non-cancerous cells (known as cancer-associated fibroblasts or CAFs).

They found CAFs talk back by sending back their own signals to help the cancer cells become drug-resistant and enter a dangerous state the experts call ‘stem-like’.

Experiments were able to disrupt the hotline between CAFs and cancer cells by using a drug called SMOi, which targets CAFs and stops them from pushing tumour cells towards a ‘stem-like’ state.

In mouse models of triple negative breast cancer, treatment with SMOi reduced the spread of cancer, slowed tumour growth, increased sensitivity to chemotherapy and improved survival.

In a clinical trial with 12 advanced triple negative breast cancer patients who had relapsed after previously being treated with chemotherapy, patients were given SMOi together with a standard chemotherapy drug (docetaxel) to determine whether the combination was tolerated by patients.

While the combination treatment did not halt cancer progression in nine patients, the disease was stabilised in two patients and tumours fully disappeared in one patient.

Researcher A/Prof Alex Swarbrick says the study is a major step forward in understanding how CAFs can drive aggressive cancer.

“It’s the stem-like cells in breast tumours that are particularly bad players, as they can travel to distant parts of the body to create new tumours and are resistant to treatment,” A/Prof Swarbrick said.

“We knew that CAFs played a role in turning cancer cells into a stem-like state, but now we know one way in which they communicate with tumours – and how to stop them talking to one another.”

Print

Print