COPD linked to workplaces

European researchers say workplace exposure to pesticides is linked to a heightened risk of respiratory diseases.

European researchers say workplace exposure to pesticides is linked to a heightened risk of respiratory diseases.

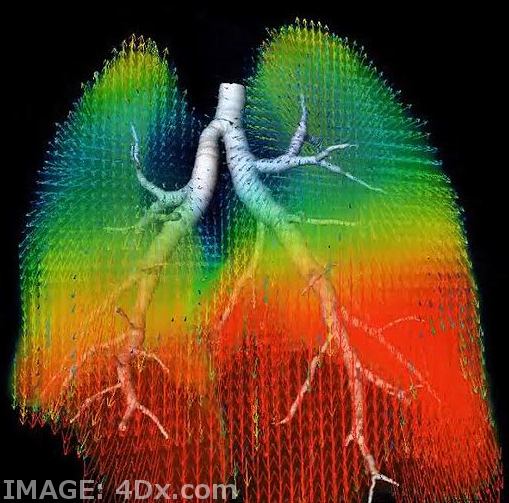

A large, new, population-based study has found lifetime workplace exposure to pesticides is linked to a heightened risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); an umbrella term for a group of respiratory diseases that cause airflow blockage and breathing problems.

Importantly, the findings came independent of other key risk factors for COPD; smoking and asthma.

It is estimated that around 14 per cent of all COPD cases are related to work, say the researchers.

They drew on data from the UK Biobank - a large population-based study of over half a million men and women recruited between 2006 and 2010 throughout the UK.

They invited a random sample of more than half a million 40–69 year olds from among Nation Health Service (NHS) patients who lived within specified distances of 22 health assessment centres in the UK to take part in their study.

At entry to the UK Biobank, personal data, including age, sex, lifetime smoking history, current employment, and doctor-diagnosed asthma, were collected and measurements of physical health taken.

These measurements included spirometry, a lung function test that measures the amount and/or speed of air that can be breathed in and out in one forced breath.

They also created a job exposure matrix to record levels of exposure to workplace agents including biological dusts, mineral dusts, gases and fumes, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, aromatic solvents, chlorinated solvents, other solvents and metals - plus two composites of the above, to include all pesticides and vapours, gases, dusts, and fumes.

The final analysis was based on 94,514 people for whom full data, good quality lung function tests, and complete job and smoking histories were available.

After accounting for potentially influential factors, workplace exposure to pesticides at any point was associated with a 13 per cent heightened risk of COPD, while high cumulative exposure (a combination of intensity and duration of exposure) was associated with a 32 per cent heightened risk.

This was further confirmed after factoring in simultaneous exposure to other agents and in additional analyses restricted to those who had never been diagnosed with asthma and those who had never smoked.

Print

Print