Dual drugs smash mouse cancer

Melbourne researchers have designed a single drug that delivers a lethal ‘one-two’ punch to several types of blood cancer in mouse studies.

Melbourne researchers have designed a single drug that delivers a lethal ‘one-two’ punch to several types of blood cancer in mouse studies.

The drug is designed to work like two cancer drugs combined.

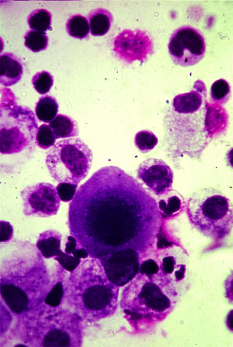

Published in PNAS, the study used preclinical models and human cancer cells in tissue culture from patients being treated for leukaemia and myeloma to investigate the possibility of dual acting drugs working as well as - if not better than - existing combined therapies.

Cancer cells are often resistant to single cancer drugs.

Combining two anti-cancer drugs with different mechanisms of action can be more effective but also problematic due to different pharmacological properties of the agents (e.g different half-lives), dosing complexity and side effects.

Researcher Professor Jake Shortt said the aim was to develop a ‘dual-acting inhibitor’ drug that acted like an effective combined therapy.

Professor Shortt said, while in its early stages, the study results were promising.

“In the best scenario, the combined effects of two drugs on cancer far exceeds what would be expected if their single activities were simply added - this is called synergy,” Professor Shortt said.

“Having identified a truly synergistic drug combination, we generated a hybrid drug that provides this dual activity in a single drug. This drug delivers a lethal ‘one-two’ punch to each cancer cell in the same place and at the same time.

“The effect is much greater than we would predict by the usual approach of combining two different drugs and minimal side effects were observed. This means we can more effectively kill cancer cells while minimising toxicity to normal cells.”

The project has focussed on blood cancers such as leukaemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Further experiments will encompass other cancer types such as breast and colon.

Co-researcher Professor Ricky Johnstone notes that synergistic drug combinations have been a cornerstone of cancer therapy for many years.

“However, our findings indicate that we can improve on this paradigm by designing drugs that are inherently synergistic on their own,” Professor Johnstone said.

“Our lead drug candidate combines just one set of synergistic activities, but we believe this approach could be broadened to encompass many different cancer targets and different cancer types.

Researcher Professor Philip Thompson, a medicinal chemist from the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS), said the program was in a pre-clinical development phase to better verify the safety and tolerability profile and hoped to move into early phase clinical trials within a few years.

“Dual acting drugs are a fascinating drug design challenge,” Professor Thompson said.

“We have captured the intellectual property rights surrounding this drug class and are looking at commercialisation options to make this available to patients into the future.”

Print

Print