HIV vaccine tests well

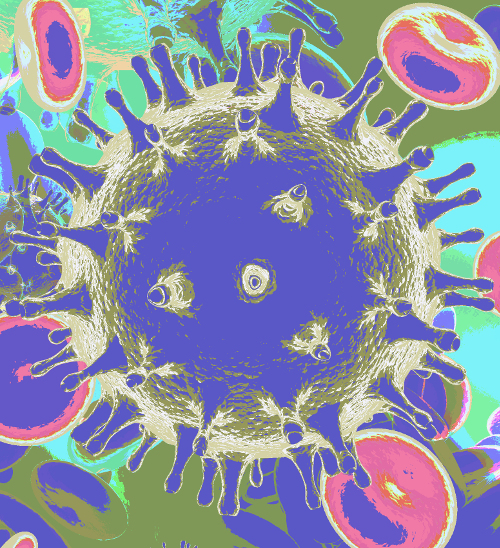

A Phase 1 clinical trial has provided promising results for a HIV vaccine.

A Phase 1 clinical trial has provided promising results for a HIV vaccine.

International researchers say their new vaccine, tested in humans, elicits the creation of broadly neutralising antibodies (bnAbs), which can recognise the globally diverse strains of HIV, and could protect against infection.

They say this trial induced bnAb-precursor responses in 26 of the 27 vaccine recipients (97 per cent).

One of the key challenges towards achieving this goal is that bnAbs rarely develop during infection, and, in humans, bnAb-precursor B cells are rather uncommon.

But researchers have shown in results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1 clinical trial that a germline-targeting priming immunogen is safe and feasible, and induced bnAb-precursor responses in 97 per cent of vaccine recipients.

The germline-targeting, self-assembling nanoparticle immunogen, eOD-GT8, was used to present 60 copies of an engineered HIV envelope protein containing mutations designed to enhance its affinity to recruit rare bnAb precursors.

“This is exciting news, especially for those people who have borne the brunt of the HIV pandemic - indigenous people, women, people in resource poor countries,” says health expert Associate Professor Clive Aspin.

“Now is the time for these researchers to be planning how this vaccine will reach these people and contribute to a reduction in the HIV disparities we see around the world, including in New Zealand and Australia where the indigenous peoples of both countries experience worse HIV outcomes than others.

“The recruitment process for this study suggests the researchers need to build effective engagement with adversely affected communities to ensure that the vaccine roll-out achieves its maximum impact and reaches those communities that are in greatest need of a vaccine.

“The science behind the development of this vaccine is important but just as important is the engagement with affected communities, especially those which have been most affected.

“It is sobering to think that this clinical development has been 30-plus years in the making and that scientists have devoted their entire careers to this approach.

“One would hope that the same amount of time and energy has gone into effective implementation once the breakthrough has occurred.”

More details are accessible here.

Print

Print