New cancer targets emerge

Australian research has identified two new potential therapies for childhood and common cancers.

Australian research has identified two new potential therapies for childhood and common cancers.

The study undertaken by Children’s Medical Research Institute in Sydney and St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research (SVI) in Melbourne, uncovered a mechanism of cancer survival.

The discovery has led to two new potential treatment options that could help kill aggressive cells that lead to both rare childrens’ cancers and common cancers.

“Cells divide throughout our lives to ensure our bodies can keep on functioning; but as they divide, the structures found at the ends of chromosomes called telomeres, get shorter and shorter, until the cell eventually dies,” said senior author, Associate Professor Hilda Pickett from CMRI in Sydney.

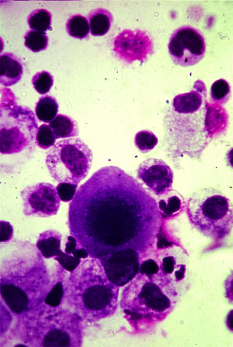

Cancer cells avoid this limitation using one of two approaches to repair the chromosome, the first is for the enzyme telomerase to be activated to add new telomeres to the DNA ends.

The second option is a process called “alternative lengthening of telomeres”, or ALT, which copy/pastes telomere DNA from chromosomes with long telomeres onto those with short telomeres.

“About 40 per cent of soft-tissue cancers including osteosarcoma (bone cancer), liposarcoma (a cancer originating in fat cells), and angiosarcoma (blood vessel cancer), as well as 10 per cent of other carcincoma cancer types, such as breast, ovarian and prostate, occur when the ALT process is activated and the cells become ‘immortal’ and cancerous”, said co-first author Dr Julienne O’Rourke from SVI in Melbourne.

“There are currently no specific therapies for ALT-positive sarcomas.

“People with this type of cancer have a 50 per cent higher rate of death, as these cancers are more resistant to current treatments.”

Researchers studying the mechanics of ALT cancers have identified a protein that is essential for ALT cell viability. Depletion of the protein FANCM is specifically toxic to ALT cancer cells.

By disrupting the function of FANCM, researchers found they could put the cancer under so much stress that it stopped proliferating.

Other studies have revealed that ALT-positive cancer cells die when FANCM is deleted.

“Both studies … found that absence of the FANCM enzyme ‘hijacks’ the ALT process and causes very specific cancer cell killing,” said co-senior author Associate Professor Andrew Deans from SVI.

“The FANCM enzyme is not essential in normal (non-cancerous) cells … this suggests it could be a good target for new drugs that could eliminate cancer cells, without eliminating other healthy cells.”

“Further, we found that FANCM could be inhibited with specific peptides, or an experimental drug called PIP-199. The next step is to do new studies with these peptides and PIP-199 to get to the stage where we can begin clinical trials,” said Associate Professor Hilda Pickett.

“We’re all excited by the life-changing and life-saving potential for children and other people with these cancers; it’s not every day you make discoveries that could lead to treatments that could save not a few, but many, precious lives.”

Print

Print