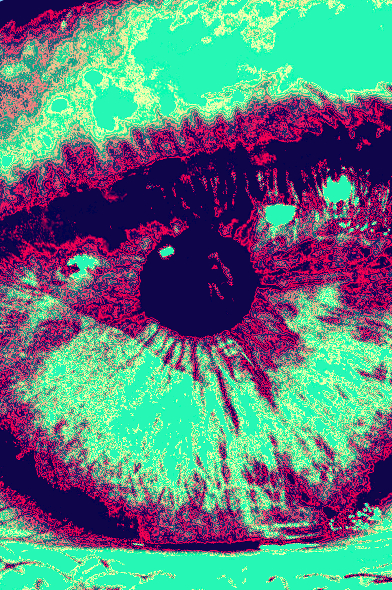

Night-eyes' origin spied

New research suggests we developed the ability to see at night to avoid being eaten during the day.

New research suggests we developed the ability to see at night to avoid being eaten during the day.

Our mammal ancestors emerged quite rapidly during the Jurassic period.

They adapted a nocturnal lifestyle when dinosaurs were the dominant daytime predator, but just how early mammals evolved night vision to find food and survive has been a mystery.

It now appears that the light-sensitive rod cells in our eyes originally developed from colour-detecting cone cells.

The research has been published here.

“The majority of mammals have rod-dominant retinas, but if you look at fish, frogs, or birds, the vast majority are cone-dominated - so the evolutionary question has always been; ‘What happened?’” asks Anand Swaroop, a retina biologist at the UK’s National Eye Institute.

“We've been working for a long time to understand the fundamental mechanisms behind rod and cone development.”

Previous work by Swaroop and colleagues showed that a genetic transcription factor called NRL pushes cells in the retina toward maturing into rods by suppressing genes involved in cone development.

“We began to wonder if, somehow, the short-wavelength cones were converted into rods during evolution,” says Swaroop.

To investigate the origin of rods in mammals, Swaroop and his team examined rod and cone cells taken from mice at different stages of development.

Details of an organism's embryonic development often reveal traits carried by its evolutionary ancestors; consider, for instance, how human embryos initially develop gill-like slits and a tail.

The researchers saw that in early stages, two days after the mice were born, developing rod cells expressed genes normally seen in mature short-wavelength cones (which are used in other animals to detect ultraviolet light).

When the researchers examined the epigenetics of purified rod cells from mice, they saw that these aspects became repressed by histone and DNA methylations later in development, ten days after the mice were born.

In zebrafish, which are diurnal and cone-dominated, another set of experiments showed that the rod cells did not resemble cones at all.

To investigate when the mammalian elements that turn cones to rods might have originated, the researchers reviewed the DNA of a variety of vertebrate animals.

The team discovered that the genes responsible for the regulation of NRL became more refined in the placental mammals as the modern retina evolved and were lost in several non-mammalian groups.

The origin of this regulatory system appeared to coincide with the evolution of nocturnality in early mammals.

The team concluded that in mammals, the transcription factor NRL became restricted to the photoreceptors in the eye, forcing the cells to change from cones to rods and giving early mammals the edge they needed to take up an active night life.

Counter-intuitively, humans now depend more on cones for vision, but that is because our ancestors later evolved to take advantage of the daylight hours again.

"These rod photoreceptors retain the molecular footprint of short-wavelength cones," says Swaroop.

"We've provided evidence that by acquiring the regulatory elements for NRL to shift short-wavelength cones into rods, early mammals changed one type of cell from capturing UV light--which isn't necessary at night--to something that is just extremely sensitive to light."

Print

Print