Study seeks psychiatric psilocybin

A small study suggests magic mushrooms could help with treatment-resistant depression.

A small study suggests magic mushrooms could help with treatment-resistant depression.

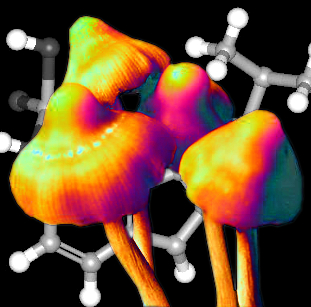

A pilot study in the UK saw 12 patients with treatment resistant depression given psilocybin - a hallucinogenic compound derived from magic mushrooms.

The drug reduced symptoms of depression in about half of the participants at 3 months post-treatment.

For all participants, it appeared to be safe and well-tolerated.

But the authors warn that strong conclusions about the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin will have to wait.

The study has been published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry.

“This is the first time that psilocybin has been investigated as a potential treatment for major depression,” says lead author Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, from Imperial College London.

“Treatment-resistant depression is common, disabling and extremely difficult to treat.

“New treatments are urgently needed, and our study shows that psilocybin is a promising area of future research. The results are encouraging and we now need larger trials to understand whether the effects we saw in this study translate into long-term benefits, and to study how psilocybin compares to other current treatments.”

“Previous animal and human brain imaging studies have suggested that psilocybin may have effects similar to other antidepressant treatments,” says fellow researcher Professor David Nutt.

“Psilocybin targets the serotonin receptors in the brain, just as most antidepressants do, but it has a very different chemical structure to currently available antidepressants and acts faster than traditional antidepressants.”

The trial involved 12 patients (6 women, 6 men) with moderate to severe depression (average length of illness was 17.8 years). All patients had previously gone through two unsuccessful courses of antidepressants (lasting at least 6 weeks), while most (11) had also received some form of psychotherapy.

Patients attended two treatment days – a low (test) dose of psilocybin 10mg oral capsules, and a higher (therapeutic) dose of 25mg a week later.

Patients took the capsules while lying down on a bed in a room with low lighting and music, monitored by two psychiatrists.

Patients had an MRI scan the day after the therapeutic dose. They were followed up one day after the first dose, and then at 1, 2, 3, and 5 weeks and 3 months after the second dose.

The psychedelic effects of psilocybin were detectable 30 to 60 minutes after taking the capsules, peaking at 2-3 hours, and patients were discharged 6 hours later.

No serious side effects were reported, and expected side effects included transient anxiety before or as the psilocybin effects began (all patients), some experienced confusion (9), transient nausea (4) and transient headache (4). Two patients reported mild and transient paranoia.

At 1 week post-treatment, all patients showed some improvement in their symptoms of depression. 8 of the 12 patients (67 per cent) achieved temporary remission. By 3 months, 7 patients (58 per cent) continued to show an improvement in symptoms and 5 of these were still in remission. Five patients showed some degree of relapse.

The patients knew they were receiving psilocybin (an ‘open-label’ trial) and the effect of psilocybin was not compared with a placebo.

The authors also stress that most of the study participants were self-referred meaning they actively sought treatment, and may have expected some effect (5 had previously tried psilocybin before).

They add that the study took place in a positive environment, and that patients were carefully screened (applicants were not included if they had a current or previous psychotic disorder, an immediate family member with a psychotic disorder, history of suicide or mania or current drug or alcohol dependence) and given psychological support before, during and after the intervention.

The findings lend themselves to further investigation.

“The key observation that might eventually justify the use of a drug like psilocybin in treatment-resistant depression is demonstration of sustained benefit in patients who previously have experienced years of symptoms despite conventional treatments, which makes longer-term outcomes particularly important,” says Oxford’s Professor Philip Cowen.

“The data at 3 month follow-up (a comparatively short time in patients with extensive illness duration) are promising but not completely compelling, with about half the group showing significant depressive symptoms.

“Further follow-ups using detailed qualitative interviews with patients and family could be very helpful in enriching the assessment.”

Print

Print